Portraits in the Age of Revolution, 1760-1830

Royal Academy, 2007

This

exhibition is organised around a central claim: that the Enlightenment produced

clear and enduring changes in the way people saw themselves and their world,

and that these changes were expressed in the portraiture of the time.

This

exhibition is organised around a central claim: that the Enlightenment produced

clear and enduring changes in the way people saw themselves and their world,

and that these changes were expressed in the portraiture of the time.

The curators suggest a division between two dramatically separate ages. The first is doomed: an ancien regime of monarchies reigning by divine right at the pinnacle of a rigid aristocracy. Its successor is triumphant: a progressive meritocracy of scientific knowledge led by a political class marching to the tune of republicanism and democracy. Rationality is victorious; religious superstition and mute obedience to authority is cast down.

Such is the thesis. The exhibition attempts to show how this revolutionary change was expressed in the public images made of the people of the new age.

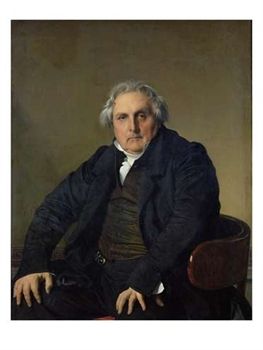

How? Firstly, the curators highlight a stylistic shift. Fussily busy interiors give way to plain backgrounds of gray and brown. Ornate props symbolising status and authority are relegated; instead a new, unadorned clarity throws the individual into sharper focus. In art-historical terms, the show attempts to document, in context, the move from Rococo and the fag-end of the Baroque into Neoclassicism. Alongside this stylistic shift, the new portraiture is characterised by a revolution in the presentation of the sitter. Throughout the show, the curators encourage a sense of an establishment taste of stale formality and preoccupation with assigned roles, swept away in a quest for informality and authenticity. Works from the ancien regime are thinly represented, for the obvious reason that the show's concern is elsewhere.  Of those present, however, Callet's 1779 portrait of Louis XVI (the most high-profile casualty of the age of revolution) fits the argument most neatly. This is a picture not of a man, but a role. Louis is shown as an embodiment of state power, in ermine-lined robes in front of a gilded throne, with the crown and sceptres that symbolise his status propped beside him. The other side of the argument is illustrated by two works that bracket the period: Pigalle's sculpture Voltaire Naked (1776) and Ingres' portrait of Louis-Francois Bertin (1832). Voltaire has beady eyes and scrawny legs. He's nude, with only a piece of his writing serving as a figleaf. His frail body is shown with realism, his engaging character with sympathy. At the same time, the sculpture praises an ideal of the pre-revolutionary Enlightenment – unpretentious authenticity – and presents it as a public monument, paid for by the subscriptions of a circle of influential admirers. The exhibition closes with Ingres' Bertin, where the solid, powerful presence of an influential newspaper editor, hands planted on thighs in a pose of no-nonsense practicality, becomes symbolic of a new class, and of a new society defined by the triumph of that class. Edouard Manet said of it, “What a masterpiece! Ingres chose Bertin to typify an epoch.”

Of those present, however, Callet's 1779 portrait of Louis XVI (the most high-profile casualty of the age of revolution) fits the argument most neatly. This is a picture not of a man, but a role. Louis is shown as an embodiment of state power, in ermine-lined robes in front of a gilded throne, with the crown and sceptres that symbolise his status propped beside him. The other side of the argument is illustrated by two works that bracket the period: Pigalle's sculpture Voltaire Naked (1776) and Ingres' portrait of Louis-Francois Bertin (1832). Voltaire has beady eyes and scrawny legs. He's nude, with only a piece of his writing serving as a figleaf. His frail body is shown with realism, his engaging character with sympathy. At the same time, the sculpture praises an ideal of the pre-revolutionary Enlightenment – unpretentious authenticity – and presents it as a public monument, paid for by the subscriptions of a circle of influential admirers. The exhibition closes with Ingres' Bertin, where the solid, powerful presence of an influential newspaper editor, hands planted on thighs in a pose of no-nonsense practicality, becomes symbolic of a new class, and of a new society defined by the triumph of that class. Edouard Manet said of it, “What a masterpiece! Ingres chose Bertin to typify an epoch.”

The curators are keen to show how new values came to dominate portraiture. “Whereas an aristocrat before the French Revolution would be decked out in a considerable amount of fancy finery, by the early 1790s everything has been stripped down to the bare essentials,” exhibition curator MaryAnne Stevens explains in the BBC's History magazine. Jacques-Louis David's 1790 portrait of the Marquise d'Orvilliers is a good example. In front of a plain background she sits wigless and without jewelery, her arm crooked informally over a chairback. Her dress is republican red, white and blue. Other pictures develop the theme. Hortense Haudebort-Lescot's 1825 self-portrait shows her in dark clothing against a plain, dark background. She has a brush in her hand, and a modest, questioning expression. It is, says the wall-ticket “a pure, unadulterated definition of herself as a working artist”. A different kind of refusal to idealise the sitter animates Ingres' striking Comtesse de Tournon (1812). With scalpel precision, in high contrast and an even light, Ingres gives us this unfortunate-looking society hostess, bug-eyed and leering. In each case, so the argument goes, the desire is to engage more directly with the individual, a desire spurred by the shifting temperament of the times.

The different treatment of established subjects was accompanied by the evolution of new subjects. The curators interestingly devote much space to showing how family life, motherhood and childhood developed as subjects for portraiture. Reynolds' picture of Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire with her infant daughter (1784-6) reflects the voguish impact of Rousseau's Emile on attitudes to children. Joseph Wright of Derby's Three Children of Richard Arkwright with a Goat (1791) shows the same influences at work on the new classes emerging in the provinces with the beginnings of industrial capitalism. Most intriguing is a group portrait of an unknown French family dating from around 1810, by an unknown artist. Reading once more from the wall-ticket: “This informal portrait is emblematic of the stalwart and upwardly mobile democratic family unit in the emergent French Republic.” Uniquely in the show, the picture's subjects aren't aristocrats or hauts bourgeois. The group is arranged around the central figure of the father, who has advanced himself and his family through local politics. These people – who twenty-five years before, if they had been painted at all, would have been depicted as rustics, firmly positioned in safely conservative vistas of rural life – are shown, in accordance with the values and ideals of a changed society, as proud, respectable, self-aware and self-reliant. The picture is the clearest illustration of the exhibition's premise (quoting from the RA's press release) that “shifts in social ideals and the emergence of new philosophical premises, most importantly, the autonomy of the individual ... resulted in changes in the role and style of portraiture.”

And yet the picture also points to an unacknowledged problem with the curators' case. While the portrait is firmly unpretentious, it is at the same time fiercely aspirational. It is a presentation of the self for public consumption. Just as ancien regime portraits cast their subjects in the context of the values of their time (emphasising wealth, lineage, piety, martial virtue), the works on display in this exhibition show individuals using their access to portraiture to create images establishing their status among their contemporaries in the society of their time. The values of that society have changed, as the exhibition successfully shows, but the role of portraiture, arguably, remains far more constant.

Houdon's bust of Benjamin Franklin (1778) supports the point. Here is newly-independent America's ambassador to Paris, wigless, modest and plain. Taking our cue from his likeness, we assume he is plain-spoken and plain-dealing. Yet hanging nearby, David Martin's portrait from a decade previously – showing Franklin in London, bewigged, in front of a bust of Newton – provides a telling contrast. He arrived in France to engineer an alliance against Britain to preserve independence. He adopted his plain appearance in conscious contrast to the decorated emissaries of established nations, as a deliberate act of public diplomacy. As one social historian puts it, “Franklin was an honest dissembler, faithful to what he believed but skilled in manipulating appearances to gain it.” His use of portraiture was part of that effort.

If its role changes less than claimed, how about the style of portraiture? As discussed, the curators base their case on the emergence of neoclassicism. The clarity and simplicity of the new style swept away the encrustations of baroque in the same way that the rationality of the Enlightenment replaced the superstitions of the past. And yet many of the supposed defining characteristics of old world portraiture survive into the new.

The most glaring example of this is Ingres' monumental portrait of Napoleon. Critics cite van Eyck's Christ the King as a model; it also seems to recall the polished stiffness of a gothic icon. These unlikely precursors point to the painting's political purpose. Napoleon was a general in the revolutionary army who seized power in a military coup and was now installing himself as Emperor. He was severely short of legitimacy, and Ingres' portrait shows him raiding the past for every last shred. He wears the laurel wreath of a Roman emperor. In one hand is the Bourbons' royal sceptre shown in Callet's Louis XVI (which hangs alongside); in the other is Charlemagne's sceptre, which includes a small figure of Charlemagne in an identical pose to Napoleon's own. The portrait is a claim to authority drawing on the symbolism of the past in a manner every bit as blatant as the ancien regime images criticised by the curators. Admittedly, Ingres' picture was controversial when unveiled and was slated by some contemporary critics as a betrayal of Enlightenment ideals. Yet in style it is inescapably neoclassical – sharp and crisp in an even light. And its contrived composition reflects Napoleon's dubious claim to be an embodiment of the age (“the Enlightenment on horseback”): he appears as the rational hub of an intricate clockwork universe.

The most glaring example of this is Ingres' monumental portrait of Napoleon. Critics cite van Eyck's Christ the King as a model; it also seems to recall the polished stiffness of a gothic icon. These unlikely precursors point to the painting's political purpose. Napoleon was a general in the revolutionary army who seized power in a military coup and was now installing himself as Emperor. He was severely short of legitimacy, and Ingres' portrait shows him raiding the past for every last shred. He wears the laurel wreath of a Roman emperor. In one hand is the Bourbons' royal sceptre shown in Callet's Louis XVI (which hangs alongside); in the other is Charlemagne's sceptre, which includes a small figure of Charlemagne in an identical pose to Napoleon's own. The portrait is a claim to authority drawing on the symbolism of the past in a manner every bit as blatant as the ancien regime images criticised by the curators. Admittedly, Ingres' picture was controversial when unveiled and was slated by some contemporary critics as a betrayal of Enlightenment ideals. Yet in style it is inescapably neoclassical – sharp and crisp in an even light. And its contrived composition reflects Napoleon's dubious claim to be an embodiment of the age (“the Enlightenment on horseback”): he appears as the rational hub of an intricate clockwork universe.

Ingres' Napoleon may be atypical. But the notion that the period encouraged rejection of artifice and a direct connection with the real, the contemporary, the authentic, is belied by other evidence throughout the show. MaryAnne Stevens claims that portraits of the period moved away from depending on “additional attributes” - symbols of status and authority. Yet Reynolds' self-portrait of 1778-80 shows the artist dressed up as an Oxford academic, defensively flourishing his honorary degree. One might argue that the Reynolds isn't purebred Enlightenment; John Singleton Copley's Samuel Adams (c.1772), though, and Gilbert Stuart's George Washington undoubtedly are. In the first, the founding father points melodramatically at the seals of the state of Massachusetts and at his own petition protesting the Boston Massacre; in the second, the first President, surrounded by symbolism including a rainbow, leans on a desk containing copies of the constitution of the United States. The “additional attributes” may have changed form, but they remain the indispensable tool of portraiture they always were. Indeed, in its constant invocation of classical Rome (a role model for contemporary republicans), Enlightenment portraiture adds a whole new register of old-style references to dramatise the cast of characters it portrays. A bust of George Washington (executed as part of a commission for an equestrian statue) shows him as a Roman senator, a centurion's armour peeping from beneath his toga. Joseph Boze's portrait of Mirabeau, the great orator of the early Revolution, shows him in 18th century dress, but everything else in the picture is utterly classical: the Doric columns, the robed statues of France and Liberty, the bas relief of the goddess Minerva (wisdom) dictating the Rights of Man. Karl Marx's famous remarks about history repeating itself as farce included the following observation:

The tradition of all the dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brain of the living. And just when they seem engaged in revolutionizing themselves and things, in creating something that has never yet existed, precisely in such periods of revolutionary crisis they anxiously conjure up the spirits of the past to their service and borrow from them names, battle cries and costumes in order to present the new scene of world history in this time-honoured disguise and this borrowed language. [Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, 1852]

Portraiture's response to the Enlightenment cannot therefore be cleanly separated into a neat before and after. Yet surely the curators' larger claims about the impact of the Enlightenment on the individual's place in society hold water? They see the Enlightenment as a period of progressive advance. The heroes are the philosophes and the encyclopédaires, the bourgeois reformers of the Estates General and the scientific pioneers who laid the foundations of the modern age. The Enlightenment citizen is seen as our revered ancestor, prototype for our cherished selves. Robert Rosenblum, the Guggenheim impresario who curated the American end of the exhibition before his recent death, suggests that our ability to empathise with the recognisably human individuals in these portraits offers the modern public an opportunity for “nostalgic retrospection”.

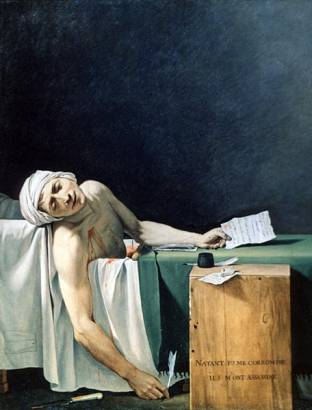

Yet the period is historically controversial. Unacknowledged is a competing strain of criticism that views in the Enlightenment the seeds of authoritarianism. David's Oath of the Horatii (1784, not part of the exhibition) strikes the modern viewer as the clearest example of the way in which republican values shade into totalitarianism. It shows the virtuous subordination of ties of family and sentiment to the superior claim of patriotic duty to the state – and it has Mussolini-style salutes thrown in as a bonus.  In the Royal Academy, we have the same artist's masterpiece Marat Assassinated (the image on the right is the version shown in the exhibition, a contemporary copy by the artist himself; the original stayed put in the Louvre). According to Simon Schama, Marat was “the most paranoid of the Revolution's fanatics ... But for David, Marat isn't a monster, he's a saint. This is martyrdom, David's manifesto of revolutionary virtue.” On completion, the canvas was paraded through the streets ahead of a weeping mob. Reproductions, turned out on the same presses as Marat's pamphlets, sold in their thousands. The painting comes with a fullblooded and highly partisan agenda: it is portraiture as propaganda. The “additional attributes” are all there: the broken quill; Marat's compassionate instructions to compensate a soldier's widow; the assassin's deceitful letter of introduction; the medicinal bath, transformed into a kind of sepulchre. So too is the use of an established language of past images: Marat's corpse, with its distorted shoulder and collarbone, is not painted from life but is a carefully arranged composition, strongly recalling a renaissance pietà. The top half of the painting is empty space, emphasising the bald fact of the assassination: divine retribution won't be forthcoming. The rallying cry – “Not having been able to corrupt me, they killed me” – printed in capital letters on the side of Marat's humble writing-desk points to the retribution required in the here and now. So, in one of its central works, chosen for use on its promotional posters, the exhibition doesn't offer us the advertised warm bath of pleasant self-recognition. Instead, through ears dulled by two hundred years of distance, we are listening to an extremist faction's histrionic call for blood feud.

In the Royal Academy, we have the same artist's masterpiece Marat Assassinated (the image on the right is the version shown in the exhibition, a contemporary copy by the artist himself; the original stayed put in the Louvre). According to Simon Schama, Marat was “the most paranoid of the Revolution's fanatics ... But for David, Marat isn't a monster, he's a saint. This is martyrdom, David's manifesto of revolutionary virtue.” On completion, the canvas was paraded through the streets ahead of a weeping mob. Reproductions, turned out on the same presses as Marat's pamphlets, sold in their thousands. The painting comes with a fullblooded and highly partisan agenda: it is portraiture as propaganda. The “additional attributes” are all there: the broken quill; Marat's compassionate instructions to compensate a soldier's widow; the assassin's deceitful letter of introduction; the medicinal bath, transformed into a kind of sepulchre. So too is the use of an established language of past images: Marat's corpse, with its distorted shoulder and collarbone, is not painted from life but is a carefully arranged composition, strongly recalling a renaissance pietà. The top half of the painting is empty space, emphasising the bald fact of the assassination: divine retribution won't be forthcoming. The rallying cry – “Not having been able to corrupt me, they killed me” – printed in capital letters on the side of Marat's humble writing-desk points to the retribution required in the here and now. So, in one of its central works, chosen for use on its promotional posters, the exhibition doesn't offer us the advertised warm bath of pleasant self-recognition. Instead, through ears dulled by two hundred years of distance, we are listening to an extremist faction's histrionic call for blood feud.

This is an ambitious show, with a declared agenda. I have outlined some of the problems, but there is nonetheless much to be said for the curators' approach. Of course, in attempting to cover two continents over a period of seventy hugely eventful years, a straightforward thesis risks oversimplifying a more complex and nuanced picture. But it is to the credit of this exhibition that its difficulties and internal contradictions are on clear display in the works on show. Part of the enjoyment of this exhibition lies in trying to sort out these tangled threads.

review by Rob Meinhard, April 2007

bonus YouTube link:

watch

Andrew Graham-Dixon tour the exhibition for the BBC (8 minutes)

watch

Andrew Graham-Dixon tour the exhibition for the BBC (8 minutes)